I watched a marketing webinar last night.

It was free. Typical of that genre, the point was to give away some information but sell you on a product or service that will give the rest of the picture. That seems a good trade off considering their time and effort put into the creation of the webinar. In return, learning from their experience made my time and effort watching it worthwhile. That’s a fair market return.

The presentation wasn’t interactive other than the pop up order form at the end. So it was basically a recording, once produced it can be repeated with only the additional broadcast cost. From what I can tell, it is played twice a day, most likely for a “limited time.” The product being sold is more of the same information. More extensive knowledge and examples are digitally boxed for download. Some level of customer service is implied.

For me, it potentially could be a good product.

The topic – Marketing – isn’t my strong suit, so I make an easy, albeit skeptical, target. I might have bought it … but the price was a bit more than what I would spend. I have a technique for shopping where if I like something enough to want to purchase it, I mentally calculate what it is worth – to me. The process includes thinking about my bank balance, the relative “need” for the product or service, how long it will last, will it pay me in return, alternative resources that may or may not do the same things for more/less time and/or money. The final consideration is Quality of Life – will I be happier/faster/slower/better for having purchased it. Whether a house or a pair of shoes, I scramble all that data to run it through the gonkulator that is my brain and contrive a cost I am willing to pay.

Then I look at the price tag.

Marketing & Economics 101

Ah price point – where supply and demand meet the wealth of nations. Wrigley made a fortune from penny sticks of gum. Today’s $.99 ebook downloaded a million times is close to a million dollars (depending more on its one time set up cost.) On the other end of the spectrum, the multi-million dollar yacht salesman needs 3 to hit the annual sales target. One puts him out of business and five will hold over for another year.

Adam Smith touted that without the tethers of government interference, private monopolies, lobbyists or “privileged” entities, the free market wields the perfect price where supply and demand meet. When banana crops fail, the price of those that make it to market goes up enough to meet whomever is willing to pay for more expensive bananas.

I’m sure he would have been spellbound by the much more elaborate threading of airline flight tickets. An incredibly (I don’t use that word lightly) sophisticated algorithm cultures those seat prices like a mother hen, sub-minute by sub-minute searching databases and optimizing just how much the seat should be priced. Would Mr Smith’s contemplations and calculations hold under the intense smoothing of the pricing integral? His theories have been smeared all of the earth with both creamy taste and reputed disgust.

He would’ve been further floored with the near-zero production costs of electronic products and services, although I’m sure he’d have much to say on it. These are the elements of economic evolution that test free market capability in a global economy.

Big Data Price Point

Of course, you probably wouldn’t be here reading this unless you’re more interested in Big Data than my spending habits. This is hardly business continuing education credit either.

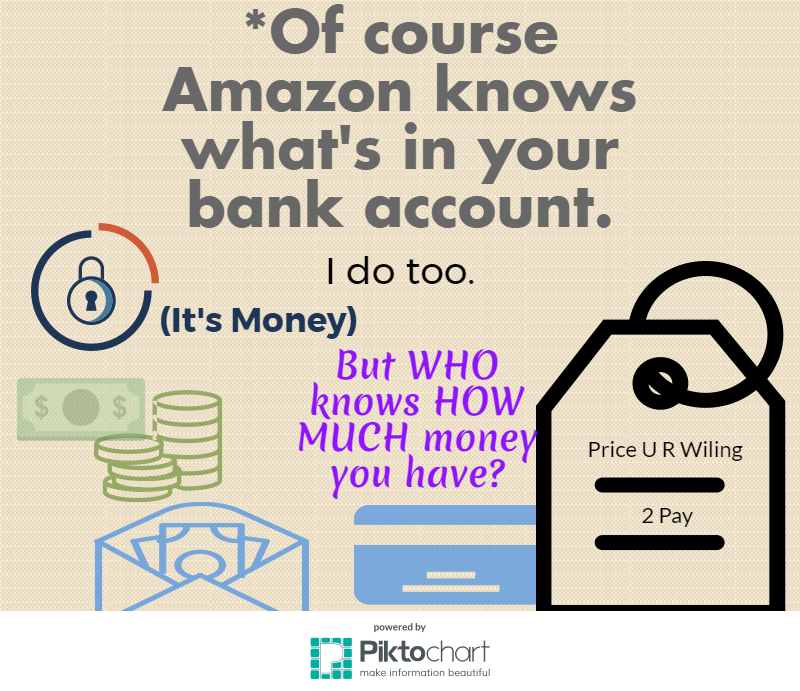

But these “small” data examples are all market driven. The future – the Big Data Price Point – is the price will shift according to your ability as much as willingness to pay. That means the webinar product that I didn’t want to pay $497 would have been further discounted to the $247 that would have made me uncomfortable but ready to use my credit card.

How is this possible? Supply and Demand. For one, it is a product with almost zero production cost. Unlike the widget which requires materials, labor, manufacturing, storage, and distribution. The digital warehouse doesn’t need a water supply or a janitor. The one stored copy (and backup) replicates instantly. There is a set-up cost; the knowledge must be conveyed creatively. People are needed to develop the product which must be marketed and maintained. The elegance of the digital effort minimizes the cost as the theoretical sales count grows infinitely. This is not a scenario Mr Smith would have anticipated.

As for demand, Big Data Price Point (PP) kicks in by knowing YOU along the same lines I mentioned that I use to make a purchase. Big Data PP would figure out if I have enough cash or credit for the sale. Big Data PP knows if I spend money on these types of products already. Big Data PP knows whether this fit my spending lifestyle or if it is a reach. Big Data PP determines if I can or cannot deduct it as a business expense. Even more so, Big Data PP calculates whether I need deductions at this point, against how many deductions I have already accrued in my fiscal year.

Big Data PP will charge me a different amount than the next sale to a different customer. An entity with a bigger bankroll may get charged more, or they may be offered a morphed package of sales for services I cannot afford: X downloads, unlimited downloads, additional webinars or custom services.

That’s not fair!

The same product is sold for different prices – because of how much I make? Well … yah. Want to write your Congressman or call your attorney? Think again.

Google (of course) is already doing it

And there are others. As early as 2000, Amazon was “price testing” multiple prices for the same DVD. They took some heat when consumers found out, so they dropped the practice (as well as the price.) In 2005, dynamic pricing came into play again when a University of Pennsylvania study noticed prices differed according browsing history – someone who had shopped competitors would get the more competitive price. In 2012, the Wall Street Journal reported how Orbitz ‘s offerings priced up to 30% higher for Mac users – Mac users have a higher income average.

Although the level of complexity may be surprising, we have become accustomed to cookies and their impact on our experience. Most don’t appreciate the impact though on the bottom line in the shopping cart.. The Atlantic explains:

the immense data trail you leave behind whenever you place something in your online shopping cart or swipe your rewards card at a store register, top economists and data scientists capable of turning this information into useful price strategies, and what one tech economist calls “the ability to experiment on a scale that’s unparalleled in the history of economics.” –

The price of the headphones Google recommends may depend on how budget-conscious your web history shows you to be, one study found. For shoppers, that means price—not the one offered to you right now, but the one offered to you 20 minutes from now, or the one offered to me, or to your neighbor—may become an increasingly unknowable thing.

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2017/05/how-online-shopping-makes-suckers-of-us-all/521448/

I’m going to need to see your zip code, ma’am

Physical or virtual, cost of living has always been tied to location. You can expect prices to be higher in New York City vice Greenbow, Alabama. I’ve known friends who won’t shop the grocery stores near their house because they are reputed to have higher prices. Then there’s the contra-pricing. I live in a resort area and to help out those of us who “suffer” through the throngs of vacationers to live the other nine months in peace, there is “locals only” pricing. That includes parking, some attractions and often secret pricing whispered over the phone ordering pizza or with the cashier for lattes.

Around the World

All the way back in the physical world, in Kenya most shopping is done in the very personal, one on one basis. Outside the upscale Village Market shopping mall in Nairobi, the Masai Market meets weekly in an open lot across the street. Advertised as an artisan fair of sorts, the goods are nevertheless likely to be found in a variety of souvenir shops anywhere in the country. It’s the experience though, another country’s version of selling what makes them unique.

I was excited. I was looking to find perhaps practical items to bring back home to share this lovely country’s culture. I was accompanied by a local. Although well-practiced at haggling from many countries around the world, I would need his native language and color to get a decent price. Otherwise, I would get the “mzungu” price, their understandable upcharge for an American, which I deserve. I didn’t expect to pay the same price as locals but I couldn’t afford the inflated price. The average monthly wage in Kenya is $76. Pricing is relative – to my location, my income, my nationality, my experience (traveler, savvy, job, education, common sense). I should pay more but not more than what the gonkulator tells me.

In the cloud

Where you live is already calculated in your costs and the virtual world does not provide escape any more than it does anonymity. My daughter realized a typical price difference phenomena when she went to college. The prices she knew from shopping online at home increased noticeably on her laptop while in Washington DC. She text a friend back home to shop simultaneously and compare. She was shocked to find the results. When she tried to change the zip code for delivery purposes – hoping to trick the system – the price refused to budge. Amazon knew where she was.

Final Morph

So pricing in the virtual world has not gone into our personal pocket books yet (that we know.) The online market does use digital information such as browsing history and location to triangulate your willingness to pay a certain price. This is still within the Small Data genre of capability, utilizing mean and median sources.

Big Data Price Point though – and I believe it will – knows YOUR personal bottom line. This is not a random variable calculated through the local and not so location population supply and demand. Big Data Price Point knows exactly what price to set for you from all your transaction history in stores and online, your taxes, your job, your household status, and much more.

Is that scary? Perhaps. But it is already very close to possible.

What would have happened with the Housing crash of the early 2000s? Big Data Price Point would have offered houses at rates that individuals could afford. Would it have curbed the domino effect or accelerated it that much more? Perhaps Big Data Price Point would have sensed the cumulative errors the isolated banks were unknowingly committing and eventually unwilling to admit. It’s a twist again for Mr Smith’s legacy to wrap around.

The world out there is waiting to sell you the next Best Thing and Big Data or not, marketing will continue to morph to find the magic price you are willing to pay. Big Data Price Point though will be oh-so intimately familiar with you and your money. In the end though, Big Data Price Point can only posture the question: will you buy?